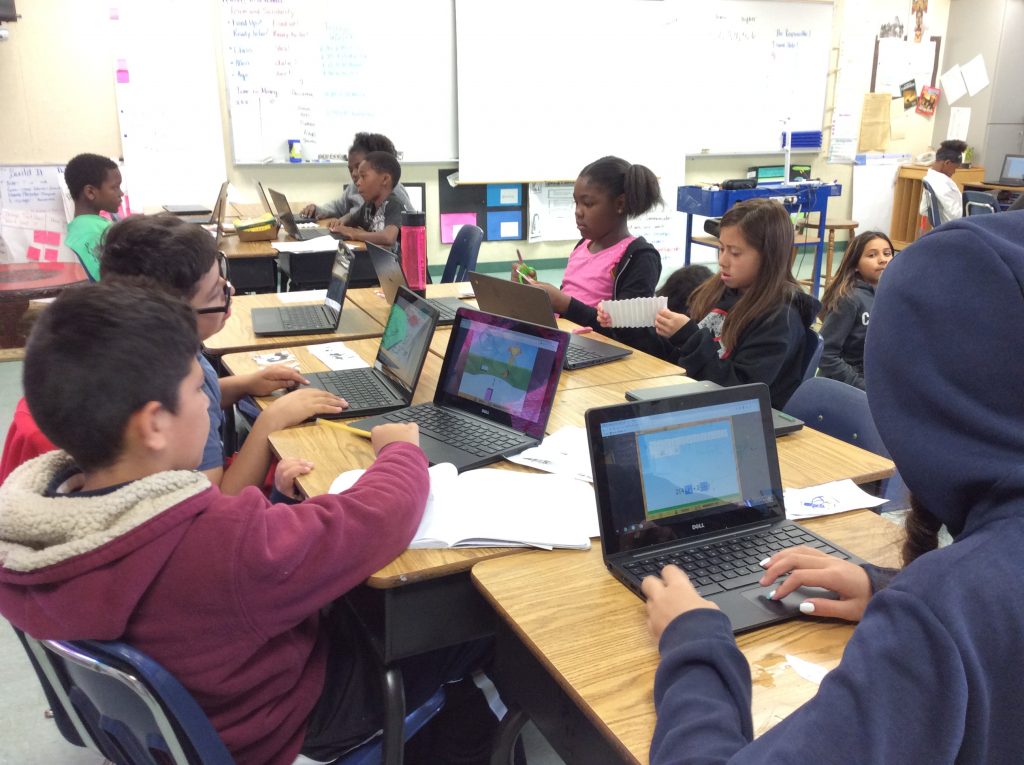

Fifth graders at Allendale Elementary in Oakland Unified use the ST Math computer program.

Theresa Harrington / EdSource

Theresa Harrington / EdSource

Fifth graders at Allendale Elementary in Oakland Unified use the ST Math computer program.

Recent news that billionaire Elon Musk is planning to buy Twitter shows how widely used tech companies can be bought, sold, changed or shut down abruptly at the whims of their owners. This should concern teachers, parents, and students: these instabilities affect not only the social media giants, but any commercial platform – including those that, over the past decade, have become vital infrastructures for the day-to-day running of public schools. .

Even before the pandemic accelerated schools’ adoption of third-party virtual learning platforms, educators already relied on these technologies to share tasks (Google Classroom), manage student behavior (ClassDojo), monitor school devices (GoGuardian), assess learning (Kahoot), and communicate with Families (SeeSaw), and Supplementing Instructions (Khan Academy). According to one study, in 2019, US counties had access, on average, to more than 700 digital platforms each month. As of 2021, this number has doubled.

As education researchers who study the impact of platform technologies in schools, we find this pattern worrisome. Education’s growing reliance on a range of privately controlled technologies is ceding enormous power to companies that are not accountable to the audience that schools are meant to serve. The deeper these platforms go into the lives of districts, schools, and classrooms, the more management, teaching, and learning are constrained to the whims of their owners.

In our work with educators, for example, we often hear complaints when an educational app pushes updates that remove favorite features or change functionality. This instability can frustrate a lesson or force teachers to restructure the unit. But the consequences could be greater with a larger company. If tomorrow Google decides to offload or close its education services, there are a few US schools that won’t be affected. And since Google is not accountable to the public education system, these schools will have no choice but to pivot to another third-party platform, which, likewise, offers no guarantee of long-term commitment to the needs of teachers and students—or, it should be noted, the security and privacy of their data.

Such assumptions might seem far-fetched, but then, the idea of Musk trying to buy Twitter seemed unlikely — until it didn’t. Confidence in the stability and benevolence of privately controlled firms in an industry notoriously volatile is the flimsy foundation upon which sustainable institutions can be built for equitable public education. We should not accept this arrangement.

While the size and influence of some platform providers may make alternatives seem unthinkable, there are steps we can and must take to make educational technologies accountable to the public schools that depend on them.

In the short term, we can question the role of these platforms in the classroom. Edtech scholars have shown how teachers can use Technical Ethical Reviews to assess how the design and use of popular technologies can work with or against their educational values or the needs of their students. Likewise, our own research shows how such inquiries can extend into lessons, as students explore the place and power of platform technologies in their own lives. Such tactics enable teachers and students to make demands on the platforms they use rather than accepting these technologies for what they are.

In the long term, we can create policies that make tech companies accountable to the public schools that use them. Adjusting procurement policies in regions, for example, can pressure platform providers to take educators’ concerns about stability, security, and privacy seriously lest they lose valuable contracts (or the usage data needed to keep their products viable). There is also scope for federal and state protections. The Digital Markets Act and the European Union’s recently proposed Digital Services Act offer one such model: creating oversight for technology mergers and acquisitions affecting public welfare and subjecting large ‘gatekeeper’ platforms to greater scrutiny. While such policies are imperfect, they provide a starting point for thinking about how to build leverage so that the privacy and stability of entire school systems cannot be determined by the business decisions of a few private companies.

If that sounds unrealistic, it is no more radical than the future privately controlled tech companies have envisioned for themselves – standing as the unregulated infrastructure for all public education. Challenging this vision requires an equally ambitious alternative: one rooted not in growth or profit, or the mercurial ambitions of tech tycoons, but in a commitment to education for the common good, and for the independence and prosperity of all students.

•••

T. Philip Nichols Assistant Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Baylor University. Antero Garcia Associate Professor of the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University.

The opinions expressed in this comment are those of the authors. If you would like to submit a comment, please review our guidelines and contact us.

For more reports like this, click here to sign up for EdSource’s free daily email about the latest developments in education.

Comments

Post a Comment